By Dr. Pravin T. Goud

Cryopreservation is often described as a triumph of modern reproductive medicine—the ability to pause biology, store potential, and resume fertility at a later time. But in practice, freezing human oocytes is far more humbling than heroic. Each egg carries extraordinary promise, yet it is exquisitely vulnerable to disruption.

Early in my research, I became acutely aware that freezing an oocyte is not simply a matter of lowering temperature. It is a biological stress test—one that challenges the structural, metabolic, and molecular integrity of the cell. Some oocytes pass that test. Many do not.

This study emerged from a desire to understand why. Specifically, we sought to understand how the composition of cryopreservation media, particularly sodium concentration, influences survival, maturation, fertilization, and early development of both immature and in-vitro matured human oocytes.

What we learned reshaped how I think about egg freezing—not as a single technique, but as a dialogue between cellular physiology and the chemistry of preservation.

Why Oocyte Cryopreservation Still Struggled

At the turn of the millennium, embryo cryopreservation had become routine, while oocyte cryopreservation remained firmly in the realm of research. Pregnancy rates were low, survival unpredictable, and concerns persisted about spindle damage, cytoskeletal disruption, and chromosomal abnormalities.

One key vulnerability lies in the meiotic spindle, a fragile microtubular structure present in mature metaphase II (MII) oocytes. Even brief exposure to suboptimal temperatures can irreversibly disrupt it. This led many to propose an alternative: freezing oocytes at the germinal vesicle (GV) stage, when chromosomes are still protected within the nuclear envelope.

But this strategy came with its own challenge—in-vitro maturation (IVM) after thawing is difficult to perfect. The question was no longer which stage is better to freeze, but how we can better support oocytes at each stage during cryopreservation.

The Overlooked Role of Cryopreservation Media

Much attention in cryobiology has focused on cryoprotective agents such as 1,2-propanediol. Less attention had been paid to the ionic composition of the freezing medium itself.

Sodium, the dominant extracellular ion, plays a critical role in cell volume regulation. During freezing and thawing, rapid osmotic shifts occur as water leaves and re-enters the cell. High sodium concentrations can exacerbate solute injury, leading to membrane and cytoskeletal damage.

Animal studies had already suggested that replacing sodium with choline could reduce these harmful solute effects. We wanted to know whether the same principle applied to human oocytes—both immature and in-vitro matured.

How the Study Was Designed

To explore this, we compared three groups of oocytes:

- Group A: GV-stage oocytes frozen in conventional sodium-based media

- Group B: GV-stage oocytes frozen in low-sodium (choline-based) media

- Group C: In-vitro matured MII oocytes frozen in low-sodium media

Sibling GV oocytes that were not frozen but matured in vitro served as controls. After thawing, oocytes were assessed for:

- Survival

- Germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD)

- Progression to MII

- Fertilization after ICSI

- Cleavage to early embryos

By using sibling oocytes whenever possible, we were able to minimize patient-related variability and focus on the biological consequences of cryopreservation conditions themselves.

What Survival Rates Revealed—and What They Didn’t

At first glance, survival rates seemed discouraging. GV-stage oocytes frozen with either conventional or low-sodium media showed similar post-thaw survival—both lower than those of frozen in-vitro matured MII oocytes.

But survival alone is a blunt metric.

An oocyte may appear morphologically intact yet still be biologically compromised. What mattered more was what surviving oocytes could do next.

This is where the differences became striking.

Low Sodium Changed What Surviving Oocytes Could Become

GV-stage oocytes frozen in conventional sodium-based media showed markedly reduced capacity for maturation and embryonic development. Even when they survived thawing, fewer underwent GVBD, fewer reached MII, and far fewer cleaved after fertilization.

In contrast, GV-stage oocytes frozen in low-sodium media behaved very differently.

Among surviving oocytes in this group:

- Maturation rates were comparable to unfrozen controls

- Fertilization rates were similar

- Cleavage rates improved significantly

In other words, low-sodium media did not necessarily save more oocytes—but it preserved the developmental potential of those that survived.

This distinction is critical. Cryopreservation success cannot be judged by survival alone.

In-Vitro Matured MII Oocytes: A Double-Edged Outcome

Oocytes froze best when they were matured in vitro before cryopreservation. Survival rates in this group were the highest of all. Cleavage per GV oocyte was also superior compared to conventional GV freezing.

Yet an unexpected finding emerged.

These oocytes showed:

- A reduced rate of normal (2PN) fertilization

- A significant increase in tripronuclear (3PN) embryos

This pattern suggests digyny—failure to properly extrude the second polar body—a phenomenon often linked to cytoskeletal disruption.

It appears that while in-vitro matured MII oocytes survive freezing well, their microfilament system may be especially vulnerable, predisposing them to fertilization abnormalities even when the zona pellucida is bypassed via ICSI.

What Happens to Cumulus Cells Along the Way

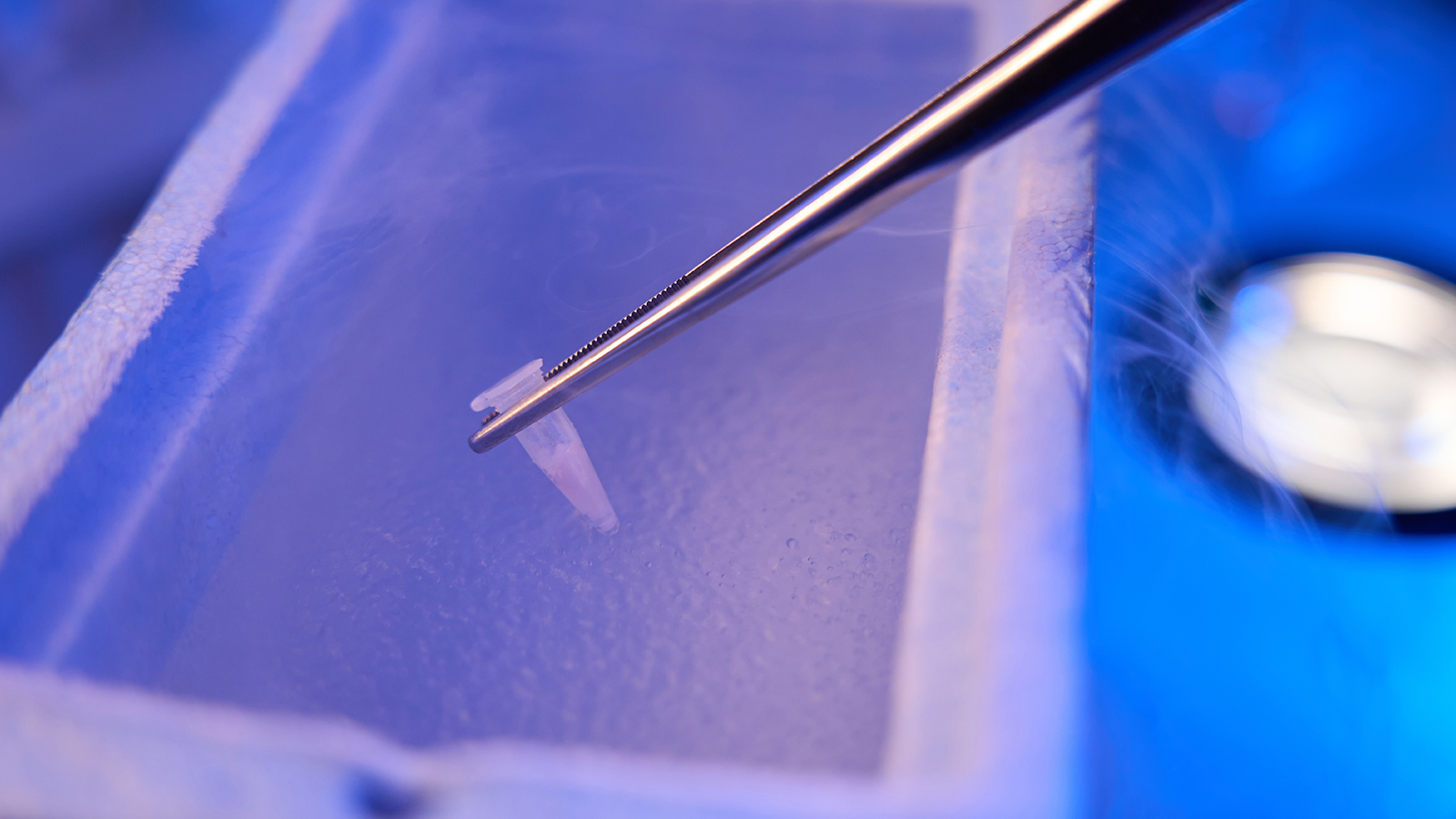

One visual detail stood out repeatedly: cumulus-corona cells rarely survived cryopreservation intact.

As shown in the micrographs (page 5), many GV-stage oocytes emerged from thawing partially or completely denuded. Those retaining tightly attached cumulus cells were often damaged, with darkened cytoplasm and abnormal morphology.

This detachment reflects the physical stress of osmotic shrinkage and swelling and further emphasizes how interconnected—and fragile—the oocyte–cumulus unit truly is.

Why Low Sodium Makes Biological Sense

Replacing sodium with choline reduces ionic flux across the oocyte membrane during freezing and thawing. This lowers intracellular solute concentration spikes, mitigating damage to:

- Cytoskeletal structures

- Organelle organization

- Membrane integrity

Our findings support Lovelock’s solute effect hypothesis—that cellular injury during cryopreservation is driven not only by ice formation, but by the toxic consequences of solute concentration.

In practical terms, the chemistry of the freezing medium can determine whether an oocyte merely survives or remains capable of development.

Lessons for Fertility Preservation

This study reinforced several principles that remain highly relevant today:

- Cryopreservation success must be evaluated beyond survival

- Immature oocytes can retain remarkable resilience when preserved properly

- In-vitro maturation and cryopreservation interact in complex ways

- Cytoskeletal maturity influences vulnerability to freezing injury

Perhaps most importantly, it reminded us that egg freezing is not a single technology. It is a sequence of biological events—each one introducing potential stress.

Looking Forward

The promise of oocyte cryopreservation lies not only in delaying fertility, but in expanding reproductive choice—for cancer patients, for those without partners, and for individuals seeking autonomy over timing.

But preserving eggs means preserving competence, not just structure.

Low-sodium cryopreservation media taught us that small biochemical adjustments can have outsized biological effects. As techniques continue to improve in fertility clinics, the future of fertility preservation will depend on respecting the cell’s internal logic as much as mastering external tools.

Freezing an egg is not about stopping time.

It’s about giving biology a fair chance to continue.

About the Author

Dr. Pravin T. Goud is a reproductive endocrinologist, scientist, and clinician whose research focuses on oocyte quality and maturation, oxidative stress, gamete biology, and the molecular pathways governing fertilization and early embryo development. His published studies have contributed to a deeper scientific understanding of egg aging, cellular mechanisms influencing reproductive outcomes, and advances in in-vitro maturation systems and assisted reproductive technologies. Dr. Goud currently serves as Chief Scientific Officer at GenPrime, where he integrates scientific innovation with evidence-based fertility care and the clinical translation of reproductive biology research.